To continue our effort to peel back the layers on the journey to passwordless, Yubico talked with former Navy intelligence officer and University of Tulsa professor, Sal Aurigemma, about his research in the behavioral information security field. Professor Aurigemma focuses on end-user experiences and adoption rates of authentication technologies. He regularly runs field experiments with undergraduates using YubiKeys to gain insight into how users who are unfamiliar with security keys and other security protocols behave in the real world.

Security managers and developers may want to take notes. Not surprisingly, it turns out that coding and meeting compliance with standards is only half the battle. You also have to get people to use the product and make it part of their lives. As Prof. Aurigemma says below, “No matter how good your tools are, the quirks of human behavior dictate that usability is paramount in any security design.”

Q: How did you get interested in the IT security space, and what took you down the road of end-user research?

A: I started out with a degree in nuclear engineering working in the Navy, and my first assignment was working on submarines. Then I moved to Navy intelligence and worked in several Navy and joint command centers. I worked in IT and got a sense of what kind of security protocols were in place.

At that time we were trying to put together a 24/7 security plan using many different protocols, and we were like MacGyver trying to keep things running. The internet wasn’t that old and IT and cyber security were nowhere near as prominent as they are now.

I was trying to secure 500 to 1,000 physical and virtual machines, and the security methods that were being developed weren’t very user friendly. I learned from that experience that if a process is too burdensome, end-users are going to find ways to get around them no matter what you do. The saying in the Navy was, “You can try to sailor-proof something, but we’ll just build a better sailor.”

The behavioral information security field is based on the concept that, assuming the user is constrained by all kinds of variables in society and life, what are the good security fundamentals that you can be confident users will actually practice? All the authentication methods in the world aren’t going to have an effect if they don’t work with the user’s routine.

Q: How does YubiKey fit into your research agenda?

A: As soon as I stopped working at a secure facility, I made an effort to look at the security landscape for my own personal use. Like many people, I’ve tried password managers and two-factor authentication (2FA), but I quickly realized how weak those methods really are. You once could trust SMS, but now it’s too easy for attackers to intercept.

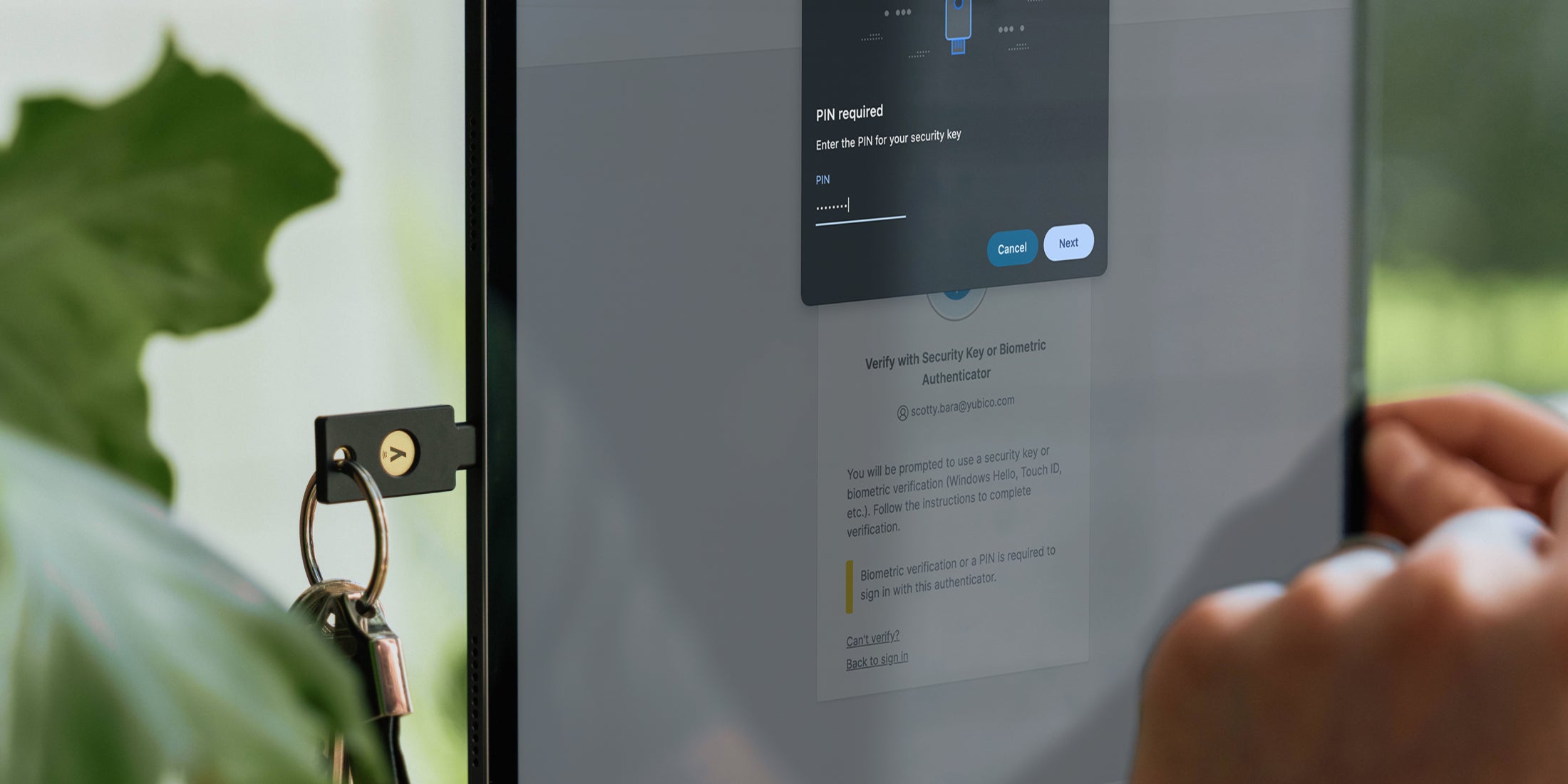

So, we live in a world where you assume there’s going to be a breach, but you should still do everything you can to not get phished. But there are very few 2FA methods that are actually phish-resistant. So when I came across YubiKey, a physical key that can’t run out of batteries, it was a “wow.” If you’re assuming breach, you need to find a technology that helps you help yourself.

Q: What can undergraduates teach us about the future of the workplace?

A: I’ve worked with more than 1,000 students now in my classes, and I think they’re a group that tells you something about the future workplace. They’re one to two years away from entering the workforce, so they’ll be using YubiKey and other protocols very soon. As an educator I can measure what their baseline is on security tools they use, then ask, what can I do to get them at or above a typical company’s expected baseline for their new employees? That knowledge is going to help them as they look for jobs.

YubiKey was a natural hardware token to use for this research because it’s so easy to use. I can introduce students to security problems, provide a solution like YubiKey, then measure what kind of adoption we see as we move through the semester.

Q: What are some of the main takeaways from your current research?

A: There are many themes that appear in the data, but here are a few of them:

- Time and resource cost are key to adoption. If a user believes that learning a new process is going to cost them a lot of time, the chances of adoption and continued use are very low. There’s often a disconnect between what the developer thinks is a significant time cost and the user’s perception. So cutting set up time is a must. There’s also a big difference on what someone does voluntarily versus if it’s a company mandate. If there’s a mandate, and an employee is getting paid to do it, they will put in the time. But you’ll probably still get low rates of continuous usage because it’s still perceived as having a high time cost.

- Articulate the threat clearly. The threat should be made personal for a user. You have to take the time to explain in a detailed and personal way, here’s the threat, and here’s why you make a good target for an attacker. Once there’s a good understanding of the threat because it’s been articulated well, that’s when you give the tools to do something about it.

- Credibility of a recommendation source encourages adoption. One thing I see is a recurring theme. When someone gets advice on security, they don’t want to hear it from the vendor. They want to hear it from their social network. They want a credible testimonial. So when you want to increase adoption and acceptance among users, having a recommendation come from a source that already has established trust is key.

Q: Do the workers of the future want to be passwordless?

A: They do, but they can’t articulate why. Fundamentally they just want to use their device. No one wants to have to take a security action. “Passwordless” is contextual, you take away the process, hide it in some hashed secret key that’s salted. It’s a layer of abstraction, providing access to a resource without an actual security action being required.

There are definitely use cases where passwordless becomes a welcome advancement for both the user and the company. Because every time you implement it, you remove the risk that’s associated with poor user behavior for those passwords.

Usability is key to good security

Professor Aurigemma’s research reminds the security community that usability matters first and foremost. Whether you’re a developer building security products or a security manager implementing them, considering your users’ behaviors — which may be defined by their demographics or their jobs — is paramount.

Are the security tools or protocols you’re implementing easy to learn and use in the context of users’ day-to-day work? Is it a seamless experience rather than one they’re tempted to circumvent? In a world where users expect frictionless systems, checking the “yes” box on those questions, is a fundamental part of the security professional’s job.

Read more about how to achieve a seamless and secure passwordless experience with YubiKeys.